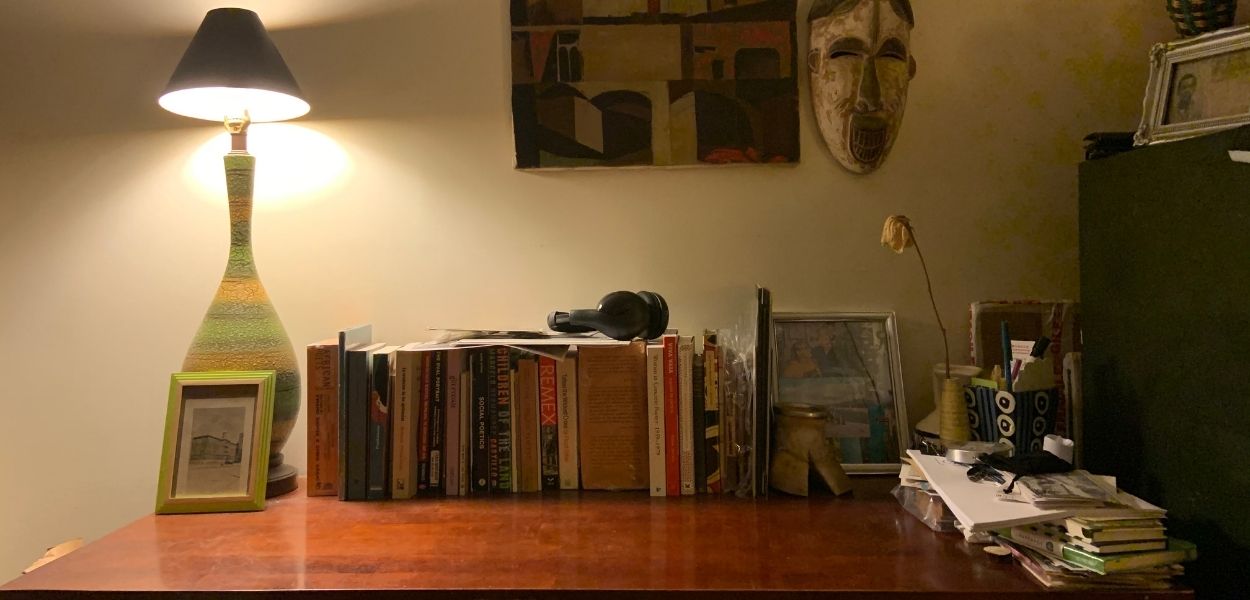

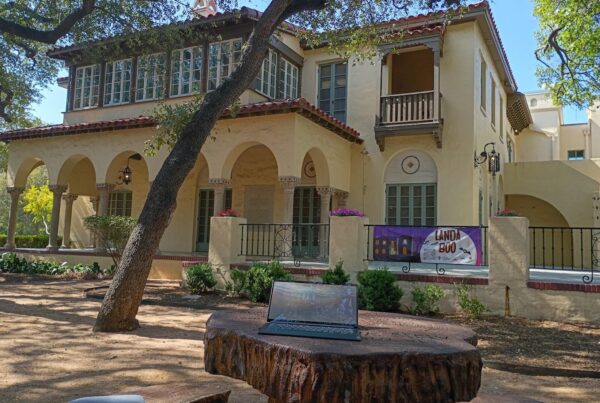

U Noel desk photo courtesy of Charlie Vázquez.

The Writer’s Desk features the desks and writing practices of Gemini Ink faculty, visiting authors, teaching artists, volunteers, students, interns, staff, partners and more. Receive new posts in your inbox by subscribing to our newsletter at bit.ly/geminiinknewsletter.

Has your preferred place to write changed over the years?

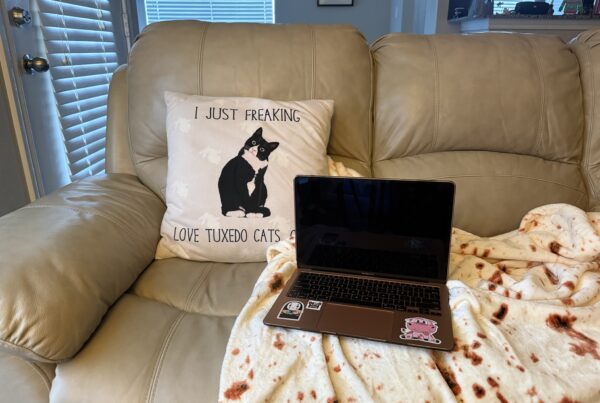

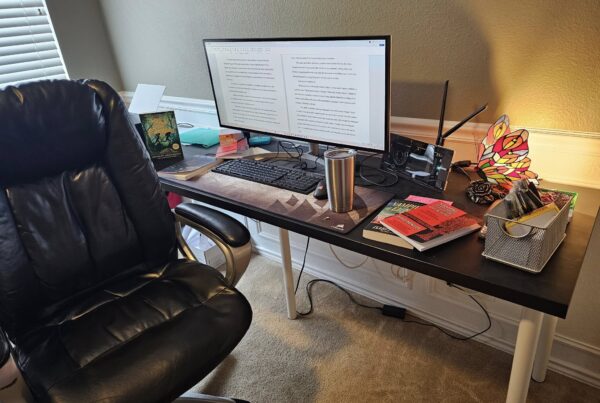

I’ve always written at home but also used to do more writing while lounging at diners and cafés. I do less of that now, partly because I have less time to lounge but also because I have a bigger place now where I can create my own lounging spaces. I use notebooks and my phone so I can also write on the go, whether commuting to work, during my regular walks, or while traveling. I also really appreciate now having a home office and a work one at NYU as well, especially when I’m on a major deadline and just need to shut myself in and crank out something big.

Do you have any habits or routines that you follow before writing?

As I mentioned, I like to have writing spaces around the house so I can switch up my routine: my office desk, the kitchen table, an office nook with a vintage typewriter (great for visual poetry), even a hammock in the backyard. I still take frequent walks in the afternoons, but now I sometimes improvise spoken poems while walking, record them on my phone, and transcribe them later.

How important is it to you to have stability in your writing routine?

It depends. If I have a major deadline, or for essays and academic writing, it really helps to have a routine and more or less stick to it. When I have a whole writing day to myself, I typically have coffee and a light breakfast, then get right to work until lunch. After lunch, I’ll take a walk and then work some more until evening (later if necessary or if I’m on a roll). I also commute to work and have traveled a fair amount, so I’ve gotten used to writing on trains and planes (buses and ferries are harder but still doable). I also spend days or weeks conceptualizing projects, where I’m reading or taking notes (or figuring stuff out while in the shower!) but not really writing. That’s still part of the process. Taking days off is definitely important: enjoying the city or nature or reading or watching something silly for the pure fun of it. Still, I’m usually doing some kind of writing during any given week, beyond the usual barrage of emails, even if just taking notes for a review or revising a draft of an essay, poem, or translation. With all the different things I do, stability is relative.

What is your secret talent? Does it ever pop up in your writing?

I don’t know that it’s secret, but I guess I have a strong sense of the musicality of language and I think that’s a big part of my writing, whether in terms of finding a fluid prose style or using a musical approach to working with poetic forms, including forms such as the décima that have a strong relationship to vernacular musical culture. That sense of musicality can also be a liability, though: it can get in the way of what I’m trying to say and make my writing too gimmicky, and when I’m translating another poet it can risk drowning out their own music. That’s one reason I like translating poets who have a strong sense of their own musicality (Edwin Torres, Wingston González) and working collaboratively. I’m currently translating Puerto Rican poet, book artist, and publisher Nicole Cecilia Delgado, and she has been great in terms of telling me straight up when the musicality of my translation sounds off or does not work with what she is trying to do—of course, she is a translator herself (English to Spanish), so she has the ear and the critical eye to rein me in as needed.

What is the one piece of writing advice that you value most?

There isn’t one in particular, but there is one I return to often. When I was starting out, I was struggling with how to put together the things I was doing on the page and in performance and trying to fit my work into all these categories. The late Pedro Pietri, foundational Nuyorican poet and mentor to many of us, told me something to the effect of: “Our people [Puerto Ricans] have been performing and doing our own poetry for hundreds of years—don’t let them tell you how it’s done.” I took this to mean I shouldn’t worry about the labels or fads and just do my thing: it didn’t have to be a book or even recognizable as poetry (Pietri did all kinds of performance and experimental works that were closer to stand-up comedy or conceptual art). It sounds obvious, but it was so liberating, and I’ve tried to honor that for all these years, although I still get hung up on categorizing things (the professor in me) and on wanting to be liked (the only child in me). It was also a reminder that calling myself a Puerto Rican poet/writer was also taking on the responsibility (and the possibility!) of embracing a range of practices and histories that might be missing from or marginal to dominant literary paradigms. One reason I perform my work and experiment with it is because I understand it can’t and shouldn’t be contained by conventions that reflect certain kinds of histories (monolingual, imperial, etc.).

Is there anything that you’ve been listening to lately—an interesting podcast, a song list, or album?

My mom suggested I listen to this old record by Las Hermanas Castillo called Voces Boricuas para América. Apparently, it was a family favorite when she was growing up in Puerto Rico. It’s got these lovely slow songs (boleros, etc.) but the two sisters’ voices have this almost operatic power that gives a different dimension to some of the more idyllic lyrics.

What theme or symbol often emerges in your work? Why are you drawn to this theme/symbol?

Probably the ocean/beach and the city. I don’t think there’s much mistery there if you know my personal geography: San Juan, Puerto Rico; New York City; San Francisco; even Melbourne, Florida (all oceanfront cities). At the same time, I think it also comes from reading poets of the city (from Baudelaire to Pietri) and Caribbean poets of the oceanic image (Aimé Césaire, Julia de Burgos).

What habit do you have now that you wish you had started much earlier?

Improvising as an exercise. My work has always been playful, and I’ve often built work around free-writing, but it was really liberating to embrace full-bodied improvisation over a decade ago and making it a regular part of my practice: I love letting the voice and body make their own meanings and learning from these exercises. It’s made me less afraid to write or say the wrong thing and more able to get out of my own head and be vulnerable.

What is your next project?

I’m working on a manuscript called Wokitokiteki, which consists of transcriptions of the vlog of the same name, where I improvise into my phone while walking around various landscapes, mainly those of places I call home (the South Bronx, Puerto Rico, central Florida). It becomes an exercise in the impossibility of truly transcribing what happened days, weeks, or even years before, partly because of the technological limitations of recording on a phone while wandering outside, but also because the time of writing is its own and there’s no going back, even when we are writing to remember or to transcribe. I’m also translating two artist books by the aforementioned Puerto Rican poet, book artist, and translator Nicole Cecilia Delgado for Ugly Duckling Presse. These two texts by Delgado use the materiality of the book to document her camping trips to islands adjacent to the main island of Puerto Rico (we’re calling the project Islas Adyacentes/Adjacent Islands), but they also reflect on the untranslatability of the experience they purport to document. In that sense, translating Delgado’s work has really helped me refine my thinking about the Wokitokiteki project.

If people want to learn more about your work, where should they go?

They can go to urayoannoel.com for general information and to wokitokiteki.com for that particular project. They can also follow @TransversalBot on Twitter, which is tweeting from my latest book of poetry Transversal once a day at 3pm EST until all the book’s poems have been tweeted (it will take well into 2022).

Urayoán Noel is the author of eight books of poetry, most recently Transversal (University of Arizona Press), which is also circulating on Twitter (@TransversalBot). His other books include In Visible Movement: Nuyorican Poetry from the Sixties to Slam (University of Iowa Press), winner of the LASA Latino Studies Book Award, and a bilingual edition of Chilean poet Pablo de Rokha, Architecture of Dispersed Life: Selected Poetry (Shearsman Books), which was a finalist for the National Translation Award. Noel’s more recent intermedia work has been exhibited at the Museum of the City of New York and published in the New York Times, World Literature Today, and on his vlog, Wokitokiteki. Originally from Río Piedras, Puerto Rico, Urayoán Noel lives in the Bronx and teaches at NYU. More information can be found on his website, urayoannoel.com.