The Writer’s Desk features the desks and writing practices of Gemini Ink faculty, visiting authors, teaching artists, volunteers, students, interns, staff, partners and more. Receive new posts in your inbox by subscribing to our newsletter at bit.ly/geminiinknewsletter.

Join Reggie Scott Young on Wednesdays 6/29, 7/6, 7/13, 7/20, 8/3, and 8/10; from 6:30-8:30pm CST, for his poetry workshop: City Songs. In this 6-week workshop, we will write poems that celebrate and critique life in the city, with a special emphasis on San Antonio and its environs. This workshop is open to writers with various degrees of experience in poetry and will focus on crafting poems for the page with an emphasis on exploring poetic forms. Guest poets, including Natalia Treviño, John Olivares Espinoza, Clemonce Heard, and Emmy Pérez, will visit the course both in-person and virtually to discuss craft issues. There will be a final celebration and open mic at Poetic Republic Cafe on August 18th.

Hi Reggie, thank you for chatting with us today. Can you describe your first writing desk for us?

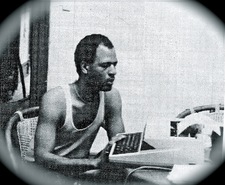

I grew up a Langston Hughes fan and remained one when I attended the University of Illinois at Chicago in the early eighties. His poems and stories helped to inspire my desire to become a writer. Many people proclaimed him a writer’s writer, and I found numerous photographs of Hughes at a desk in front of a typewriter with a manuscript in hand. Back then I failed to understand that a writer situated in front of an ornamental desk while smiling at a camera is no more than a writer posing and not an image of a writer at work.

Wanting to be like Hughes, I convinced my mother to help me purchase a desk of my own from an estate sale in Chicago’s Rogers Park, a neighborhood in which very few residents looked like me at that time in the city’s history. It was a well-used unit made of solid oak, and I hoped it once belonged to a successful writer, such as Nelson Algren. I didn’t know enough about Algren to know the author of Walk on the Wild Side probably composed handwritten drafts of his stories on Formica counters in Wicker Park diners or on bar tops in rowdy Milwaukee Avenue taverns. If you were to read Algren today, you’d understand where I’m coming from. I soon found that the main role of my vintage desk would be to collect dust in the West Side apartment in which I lived, an area of the city that I wrote about as “Bluesville.” But a place named Bluesville is not where you’d expect to find many people with desks in their apartments, and that made me an oddball in that community. I may have owned a desk, a desk I could pose in front of for pictures, but it had only a narrow opening underneath for my legs, and it sat too high for me to write on comfortably with a typewriter. There were pullout trays for writing letters, but the wooden chair it came with was difficult to maneuver from side to side without bumping my legs against its hardness. When I sat at that desk, I often felt like Houdini underwater in a straitjacket. I spent more time thinking about ways to escape than I did about writing.

Hughes’ first published poem, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” took me as a reader on a voyage through time and into other parts of the world due to his references to rivers that played significant roles in African American history. It read like a poem written while in motion, like on a train or a ship. I remember reading it one afternoon while approaching the Chicago River on an L train downtown. I later discovered Hughes wrote the poem shortly after his high school graduation while traveling by train from Ohio to visit his estranged father who lived in Mexico. The impulse that led him to draft the poem in the margins of one of his father’s letters stemmed from the creative excitement he felt as the train passed over the Mississippi River. I felt a greater sense of literary kinship with Hughes after that because I had already produced a slim volume of Bluesville poems while riding around Chicago on the L. The most authentic desk I owned during my early writing years might have been a once-proud piece of furniture that had occupied a ritzy Rogers Park home in its past life, but my most productive desk turned out to be my lap on which I rested the notebooks I wrote in while riding high above the city. Of course, I also wrote in other places such as while sitting on the front stoop of my family’s two-story brownstone, on park benches, while leaning against neighborhood walls and trees, and in the kinds of places where I imagined Nelson Algren wrote. But if a desk can be conceived of as a place where writing is performed instead of a symbolic piece of furniture, my most memorable writing desk was a seat on the L.

What about other writing desks that have been important to your work?

The summer before I enrolled in the graduate creative writing program at UIC, I acquired a more practical “desk” for my apartment, one that offered me greater freedom of movement than the dust collector in my front room. I worked at the Montgomery Ward furniture warehouse in Franklin Park, my first extended experience outside of Chicago’s municipal borders. Not only did we, as employees, receive discounts on our purchases from the warehouse’s showroom, but we also had first dibs on items marked down as “Used and Abused.” I found a table and chairs that gave a modern touch to my second story apartment. The unit also turned my dining room into a multifunctional living and

workspace. The table’s large round top sat on a base designed to look like a whiskey barrel. It came with cushioned swivel chairs. A young woman I dated at the time who came from a more affluent background, complained that the table was tacky, but I argued it was an expression of ghetto-postmodernism. While working on critical research papers for A. LaVonne Ruoff’s Native American Literature class or poems for Michael Anania’s poetry workshop, the table offered room enough for me to compose handwritten drafts while facing one of the windows. I could move to the right to type on my Brother electric typewriter in front of a steamy radiator during frigid months of winter. If I needed to work during dinner, all I had to do was shift to the left to enjoy a plate of my mother’s smothered cube steak with mashed potatoes and green beans. Since my parents lived in the apartment below mine, my mother made sure I was a well-fed grad-student writer. The poems I wrote on that table became some of my earliest publications, including the collection of Bluesville poems that I included in my master’s thesis.

workspace. The table’s large round top sat on a base designed to look like a whiskey barrel. It came with cushioned swivel chairs. A young woman I dated at the time who came from a more affluent background, complained that the table was tacky, but I argued it was an expression of ghetto-postmodernism. While working on critical research papers for A. LaVonne Ruoff’s Native American Literature class or poems for Michael Anania’s poetry workshop, the table offered room enough for me to compose handwritten drafts while facing one of the windows. I could move to the right to type on my Brother electric typewriter in front of a steamy radiator during frigid months of winter. If I needed to work during dinner, all I had to do was shift to the left to enjoy a plate of my mother’s smothered cube steak with mashed potatoes and green beans. Since my parents lived in the apartment below mine, my mother made sure I was a well-fed grad-student writer. The poems I wrote on that table became some of my earliest publications, including the collection of Bluesville poems that I included in my master’s thesis.

I soon married and to avoid embarrassing my wife, I tried to distance myself from all expressions of ghetto-postmodernism. That meant the table that also served as my writing desk had to go. In need of a more fashionable desk for my work in our new Oak Park apartment, I discovered a unit at a nearby Scandinavian Design store that I still own—or at least part of it. The desk, a sixty-four-inch Danish modern with no drawers under its laminated solid wood top, fit perfectly along the wall of the enclosed front porch that I used for my study in an apartment located blocks away from the township’s historic Frank Lloyd Wright houses and the home where Ernest Hemingway lived during his short time in that Chicago suburb. I wrote my dissertation, a multi-genre novel titled Crimes in Bluesville, on that desk using my first computer, a Kaypro that weighed as much as a crate of bricks. Unfortunately, that primitive machine couldn’t store any more than thirty to forty typewritten pages on its hard drive. Next to it on my desk were piles of the old 5 ¼ floppy disks that looked like square frisbees.

Due to frequent relocations during the years I worked in higher education, the desk found itself in the clutches of too many ruthless movers who handled its delicate frame like it was little more than discarded lumber. The support panels eventually broke, and after another move or two, the panels could no longer be reassembled with joint connector bolts, duct tape, and construction glue, leaving me with nothing but a giant slab of a desktop. I was in Lafayette, LA, by this time, on my own after my marriage suffered a fate worse than the ruin of that desk. Living in isolation while far from the place that I still identified as home, I needed to write to keep my head on straight, but my desk was now a sad amputee with no legs to stand on. Then while browsing at Louise’s Real Wood Furniture store one day, I spotted a pair of thirty-inch tall unfinished bookcases. I bought a pair with the hope that they might serve as platforms for my desktop. If you were to see them in the study of my home in San Antonio today, you’d believe that the desktop and bookcases underneath were built as a single unit.

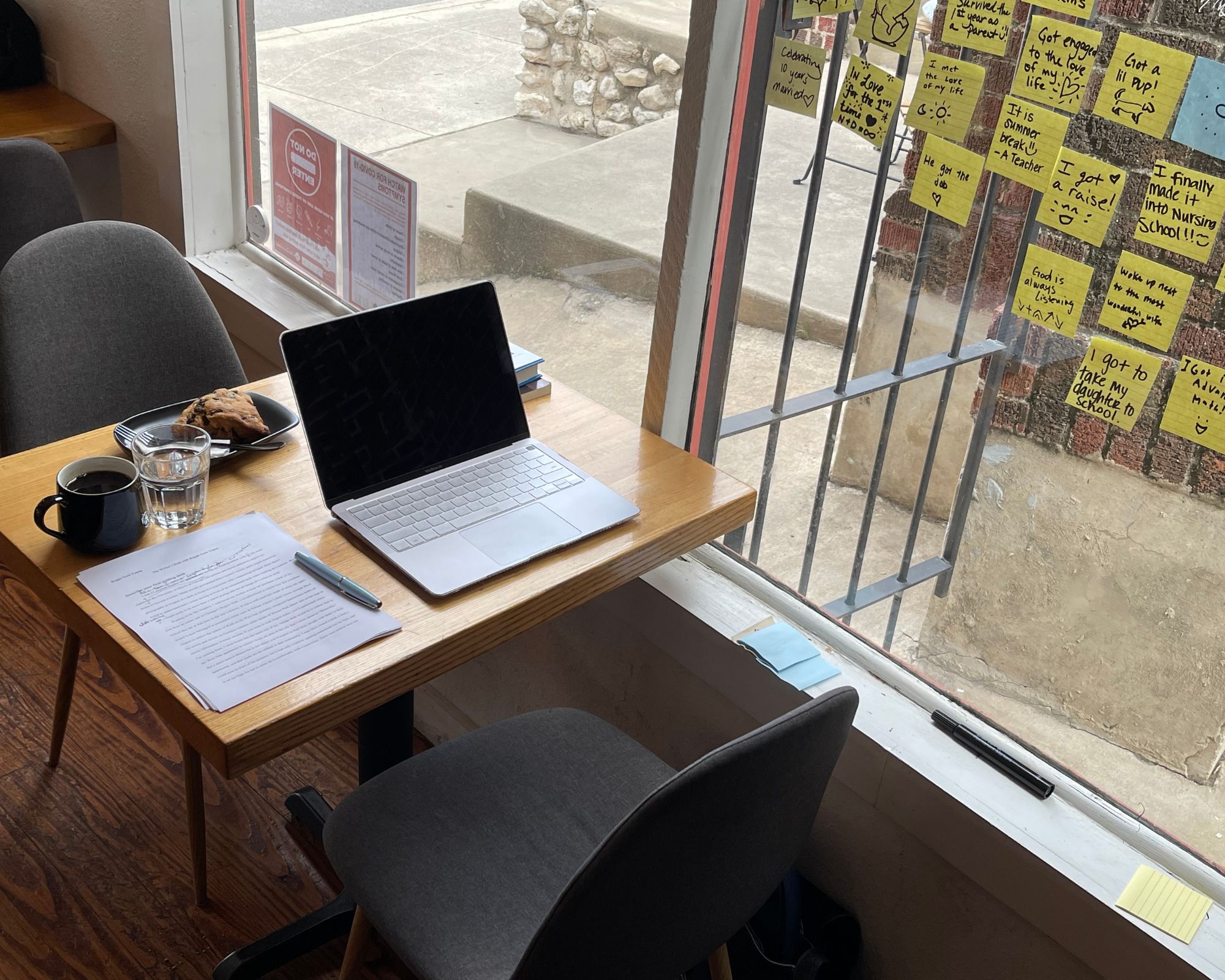

Desk today in SATX

Has your preferred place to write changed over the years?

Despite rapid transit trains, whiskey barrel tables, and Scandinavian desks, at some point I learned to do my best writing in coffee shops. Other writers can offer similar stories. My reliance on coffee shops began in the mid-nineties after I moved back to Illinois to serve on the faculty at a very conservative religious college outside of Chicago. The institution was so pious that no one who smoked, consumed alcoholic beverages, danced, identified as gay, or engaged in sex outside of marriage could attend school or work there. Despite the college’s numerous social prohibitions, what alienated me the most was the emphasis it placed on Protestant religious traditions that didn’t include great men and women of faith who looked anything like me. I still had hopes of publishing my dissertation, an urban crime novel that makes Colin Whitehead’s recent Harlem Shuffle look tame. Although I tried, there was no way I could make the narrative’s vicious murder scene palatable for conservative evangelical consumption, nor its depictions of junkies and drug use, profane language, and a sex scene that was a thousand times more provocative than the love scenes featured in old Doris Day movies. Working on a novel about a place called Bluesville in that pristine institution seemed more out-of-place than having Muddy Waters sing “Got My Mojo Working” at a Southern Baptist Convention.

With my Danish modern desk at home now situated in a musty and flood-prone basement due to a growing family, I lacked an environment conducive to academic research, paper grading, and creative production. I needed a place to work away from my home study and school office. A nearby Caribou Coffee location provided me with the creative sanctuary I needed. Besides, the coffee wasn’t bad. Since then, coffee houses have served as remote office locations for me, and in each I have claimed a particular table to serve as my writing desk. There is a marvelous café here in San Antonio that I visit almost every day, one that is especially fond of poets and writers, but I’m afraid to mention its name because someone might decide to go there and sit at my table.

Do you have any habits or routines that you follow before writing?

Many writers have rituals that are sacred to their writing process. My writing day begins with me getting up in the morning around 6:30 and going on a 5K walk near where I live through Concepción Park and along the Riverwalk between Mitchell Street and Mission Road. I consider it writing time because during my walks I compose parts of poems and stories by speaking into my phone’s voice recorder. After returning home and getting cleaned up, I head over to my favorite not-to-be-named café. Most days I order the house coffee and a pastry before I begin my work. I abhor sugar in coffee and find that a chocolate chip scone is a much better sweetener. Unlike most writers I see in coffee shops, I never order lattes or specialty drinks. I’m a poet in the truest sense of the word, meaning I don’t have much money. I find that the act of continuously sipping helps to fuel my work as much as the intake of caffeine. Most cafés offer bottomless cups of drip coffee, but not free refills of specialty drinks or cold brews. If I were to write a treatise called The Economics of Poetics, in chapter one I would advise any poet without a well-paying job or trust fund to stick to the drip, avoid espresso concoctions that often disappear while writing a single stanza or paragraph, and to wear headphones or earbuds. Unfortunately, there’s always a telemarketer working remotely at a nearby table trying to talk over the music from the café’s stereo system and the noise of grinding beans. Little of what they’re trying to sell will help in your effort to come up with a crucial metaphor about the necessity of sunflowers or the tenderness of your grandmother’s hands.

What is the one piece of writing advice that you most value?

In her poetic dedication to the unveiling of Chicago’s Picasso statue years ago, Gwendolyn Brooks exclaimed, “Art hurts. Art urges voyages—and it is easier to stay at home, the nice beer ready.” Since I’ve never been much of a beer drinker, I’ve found her advice useful. Early in the recorded history of intellectual thought, Aristotle discussed the importance of exploration in his essays on rhetoric and poetics. Taking hurtful voyages should be an important aspect of our work. Sandra Cisneros often tells young writers to “write until it hurts,” and in doing so she means write for depth instead of the amount of time spent putting words on the page. Writing entails explorations into our humanity. It requires us to look under the hood of human life and make art out of the filthy stuff that we find there. Beauty too, but don’t we also have to take voyages to find beauty in the messiness of our collective lives?

Do you like things to be carefully planned out or do you prefer to just go with the flow? Does this also apply to how you lay out a story?

I owned a record player during my youth and learned to appreciate music by improvisational jazz artists. I loved John Coltrane’s recordings of “My Favorite Things,” a song originally written for Mary Martin to sing on stage in “The Sound of Music.” Martin’s version, performed nightly as a fixed piece of music, offered a cheery melody intended for upscale Broadway audiences. Each recording of the song by Coltrane differed in length, and you could tell none of the musicians in his ensembles performed while reading sheet music. I knew a few older jazz fanatics who’d talk about how avant-garde jazz musicians would start out by playing a melodic line but then take it out to sea—like on a voyage—something I could always sense while listening to Coltrane play “My Favorite Things,” “Spiritual,” and “A Love Supreme.” That’s why I knew early on that I wanted to follow Coltrane’s influence. Not that I wanted my writing to read like a Coltrane performance, but I wanted to see where poems and stories I wrote might take me.

The Graceful Lie by Michael Petracca, a fiction handbook that I used at times in undergraduate writing workshops, included a chapter on different approaches to writing narratives that he classified as structural and organic. Without question, I knew my writing style was organic, the same as it is today. But highly organized writers who begin the writing process by scoring or constructing outlines of the stories and narrative poems they plan to write must still engage in an organic process. Even after you devise an overall structure for a piece of writing, you still have to fill it with figurative content, just as lyricists have to come up with compelling words to go with a musical score. Likewise, no matter how organic any content I come up with might be, I must engage in the hard and at times difficult work of giving it structure. My structures may appear to work more like rivers than skyscrapers on the page, but the purpose of both is to shape the flow of language.

Which words or phrases do you most overuse?

Adroit!

It’s not that I’ve used it in anything I’ve written, but if I did it would be an act of overuse. I’m sure the word is worth a beaucoup number of points in Scrabble and might show up in a New York Times crossword puzzle from time to time, but although writers should consider all words fair play, it doesn’t mean all words are appropriate.

I remember my poetry professor in grad school, Michael Anania, who now lives in Austin, used that word from time to time. He’s probably the only one I’ve heard speak the word to this day. While sitting at a workshop table in University Hall, I scratched my head the first time I heard him say it. I tried to deduce the word’s meaning from the context in which he used it, but I knew right off it wasn’t a word for me. After all, while going to church with my family as a youth I never heard the reverend say, “Lazarus was raised from the dead by the adroit hands of Jesus,” and none of the guys I played basketball with claimed to have an adroit handle while dribbling the rock.

Deft is a more functional version of the word, especially in its shortened form. After all, could you imagine Jay-Z purchasing a company named Adroit Jam Records, or rock fans flocking to an Adroit Leppard concert? I’d be excited to check out a new café named Def Coffee and Pastries but wouldn’t consider one with an Adroit Coffee and Tea sign above its doors. A place like that might turn out to be too blasé and expensive.

Anania often referred to poets from the New York school that Diane Seuss rags on in the opening poem of frank: sonnets, especially Frank O’Hara. He also talked a lot about John Ashbury and brought W.S. Merwin to our campus. They were authors of adroit works of poetry, but not the kind of poems I felt called to write. If I dropped adroit into my poem titled “The Bluesville Boogie,” it would come off sounding phony. In fairness to Anania, he directed my dissertation and encouraged my interest in writers such as Henry Dumas and Robert Hayden. He also helped bring to campus James Welch, Ishmael Reed, Carlos Fuentes, Toni Morrison, and others whom I would not associate with the word adroit.

There are certain words I do overuse, especially prepositions and conjunctions that function as mortar to the forms of nouns and verbs that serve as bricks in our writing. Those simple words are essential to our use of language. But words such as adroit are more extravagant than essential. They are bricks you’ll need to find at a place like Restoration Hardware and not Home Depot. Since I’m far from an extravagant writer, the only time I can conceive of me using adroit is to explain why I would not use it. I’ve never liked reading poems and stories by writers who confuse extravagant-looking writing for good writing—who use words like adroit when they don’t sound right coming out of their mouths. I can appreciate adroit in a Michael Anania poem because the language choice is appropriate for him. In the hands of a less adroit writer, a word of that nature stands out as a flagrant example of overuse.

What are some misconceptions about being a writer that you can discredit?

While in grad school, several of the fiction writers in our program were into Raymond Carver and under the influence of Gordon Lish’s minimalist philosophy. As a result, I found myself caught up in a holy war against the use of adverbs and other writing excesses. The thing is, I liked adverbs. I came from a culture that is especially fond of its adverbs. Nevertheless, Lish’s minimalist movement steamrolled through the institutional writing culture of the era. Writing had become about writing itself with less concern about the insights we might offer about the world in which we lived.

One of my earliest writing instructors was Mark Twain. The first complete adult novel I read was Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, and that story led me to Twain’s memoir about his days as a cub pilot in Old Times on the Mississippi. One of the paragraphs in that tale had to be two or three pages in length, and some of the sentences longer than the bridge that crosses the Mississippi when traveling from Illinois into St. Louis. He used as many semicolons as you’d find catfish in that river. Due to Twain’s early influence, I loved to write long flowing sentences, sentences as long as the Mississippi—or, at least as long as an L train ride from Chicago’s West Side to Rogers Park.

A few years later during my career in higher education, scholar Shirley Fisher Fishkin, published a book titled Was Huck Black. In it she argued that Twain was influenced by the speech of enslaved and free Black people he knew during his youth in Missouri. Those interactions served as a major influence on the vernacular language Huck spoke in a novel that was to become an American classic. Despite the numerous imperfections in Twain’s works due to the excesses in his writing, I felt myself drawn to him, as did Ralph Ellison and numerous other writers from backgrounds similar to my own. My quandary was how could I express myself like a Twain devotee and still earn a degree in creative writing alongside writers who were under the influence of Gordon Lish?

Several years later Carver and his wife, poet and writer Tess Gallagher, rejected Lish’s substantial revisions of Carver’s earlier works. They published a volume of Carver’s collected stories that included his original versions with many of the so-called writing excesses that Lish had edited out. Carver during his career produced what has become known as K-Mart or trailer park fiction, but Lish turned his stories into consumable goods for high-cultured readers of magazines like The New Yorker. My point is that writers, especially in top university writing programs and upscale workshops, are at times instructed to write in ways that will be most attractive to New Yorker readers. Like we should all write for audiences that prefer Mary Martin’s rendition of “My Favorite Things” on Broadway. I would argue that if you want to write for people who live in trailer parks, along the Rio Grande border, in Texas’s Hill Country, its Panhandle, or a community that you think of as Bluesville, respect your calling. Write about those people and places in a way that honors both them and you. Find the best way for you to express your favorite things. Never discount any instruction you are fortunate enough to receive, but only use what’s most useful for you at the time. Park the rest in the drawer of your dust-collecting writing desk. Pull it out when it becomes of value to your writing.

Reggie Scott Young grew up in Chicago and used writing to escape life in the streets. After that, he spent a quarter-century as a college and university professor. He’s published scholarly books and academic essays, but creative writing was his first love. He’s published a volume of poems, Yardbirds Squawking at the Moon, and is proud to be included in the upcoming Anthology of Chicago Poets. His poems, short stories, and works of creative nonfiction have appeared in Chicago Review, Another Chicago Magazine, Oxford American, riverSedge, and other publications.

Visit Reggie online:

www.reggiescottyoung.com

https://rycitysongs.wordpress.com

Instagram: @reggiey123

Twitter: @ReggieScottYou1